What is blocking the president's way?  By Sergei Markedonov, special to Prague Watchdog

Moscow

October 30, 2009 marked the first anniversary of the day on which Russia’s President Dmitry Medvedev signed a decree “On the early termination of the powers of the president of the Republic of Ingushetia". This legal document brought to an end the political career of Ingushetia’s second president, Murat Zyazikov, who had held the post since April 2002. At the same time, Medvedev’s decree gave a start to another career – that of Yunus-Bek Yevkurov. On October 31 2008 the republic’s parliament confirmed a military officer none too well known to the general public, the deputy chief of staff for the Volga-Urals Military District (PUrVO), in the post of President of Ingushetia.

During his first year as president Yevkurov had quite a number of successes. He moved the acute problem of the republic’s Prigorodny district onto the level of a constructive negotiating process. To this end he invited Mukharbek Aushev, an experienced businessman and political figure, to be Ingushetia’s de facto ambassador to North Ossetia (the president’s representative in the neighbouring republic). The Ingush government withdrew its demand for the return of the area that had once been part of the Chechen-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ChIASSR), and also renounced its claim to a "special regime of government" there. At the same time Yevkurov revived the issue of the return of internally displaced persons to the Prigorodny villages where they had lived before the 1992 conflict. For the first time in the post-Soviet period the problem of the "ethnic ownership of the land" was replaced by another approach, one that sought to ensure equal civil and human rights in the disputed territory.

When Yevkurov, a personnel officer and paratroop colonel who had taken part in the famous Russian grab for Pristina, took up office a year ago, he made it his special business to restore public confidence in the Ingush government. For the most part, his behaviour as head of the republic was not typical of North Caucasus leaders. For example, immediately after his confirmation by Parliament he refused to take part in a ceremonial inauguration, justifying his decision on economic grounds. During his first two months in office Yevkurov opened a dialogue with community leaders and human rights activists and undertook preparations for a Congress of the Ingush People. Many prominent secular opposition figures (whose criticism of the authorities was based within the framework of the Russian legal system) announced that they were calling off their struggle and talked of the need for constructive cooperation with the authorities. Until the autumn of 2008, the radicalization of the secular opposition and the loyalist part of the opposition spectrum had been quite real. And it is doubtful whether it would have added much stability to the smallest of the North Caucasian republics.

However, it would be wrong to cast the third president of Ingushetia in the role of a "human rights defender in uniform". Yevkurov did not remove the issue of counter-terrorism from the agenda. . On the contrary, he repeatedly called for more effective counter-terrorist measures (though sometimes his views on the nature of terrorism were striking in their oversimplification, and especially in their assumption that the United States and Israel played a decisive role in destabilizing the republic). But the Ingush president, as a military man with experience of peacekeeping in the Balkans, was well aware that only the support of public opinion can legitimize the use of force by the authorities. The indulgence of the federal centre alone (on which Zyazikov and many his colleagues relied) is not enough. Hence the need for dialogue with the public and with civil society. The second problem is the effectiveness of security measures and their use strictly within the limits of the law – the point on which a state may differentiate itself from the organizers of terrorism and sabotage.

At the same time it would be at the very least naive to expect Yevkurov to achieve a full and final reconciliation of all with all. For on thing, too many mistakes were made in the republic before him, and for another the scale of the problems that have emerged in Ingushetia during the post-Soviet period have demanded (and continue to demand) the attention of the federal centre and its resources and capabilities. Ingushetia has no large cities, and all the aspects of its social infrastructure are poorly developed. Less than half (42.5%) of the population live in cities, of which there are only four. The republic’s four rural districts contain only 37 rural settlements, but their average population is very high – 7,480. This figure is 25 times greater than the average population size of Russia’s rural settlements as a whole. Almost three-quarters of Ingushetia’s population live on 10% of the republic’s territory – in the Sunzha Valley and surrounding areas. It is obvious that all these problems cannot be solved with the resources of a small republic dependent on subsidies from the Russian state. Especially against the backdrop of the forced restoration of neighbouring Chechnya and the partially recognized South Ossetia, both financed out of the federal budget.

The same thing applies to the strategy of the fight against terrorism. Without a concerted position on the building of a common strategy for the North Caucasus (in which Ingushetia will be grouped together with Dagestan, Chechnya, and the western part of the Caucasus), any "new approaches" in a single republic will have only limited success. Moreover, the assassination attempt on Yevkurov by militants in June this year revealed an unpleasant fact: in the fight against the militants, the liberalization of the republican regime does not work. On the other hand, the more subtle fight against terrorism is far more dangerous to them, since active counter-terrorist measures coupled with an effective dialogue between government and society deprive the organizers of the “great upheavals” of their moral arguments. For the latter, the artless brandishing of police batons is much more agreeable, because together with an increase in torture and arbitrary violence it increases the number of disaffected citizens and creates a copious reserve of the “knights of TNT”.

As we can see today, it was the June assassination attempt that slowed down Yevkurov’s "new course". After the attack on the president’s car on June 22, many supporters of the "power line" felt morally vindicated. The result was a reinforcement of the state’s security elements (through the introduction of "external police control”, as well as federal officials), which partially restored the situation to that of the period prior to October 30 last year. At present this turning back of the clock is temporary in nature and can not be considered irreversible. However, the trend is there.

Fundamental changes in other matters will hardly be possible until decision-makers at the highest level realize that "systemic threats" to Russia's statehood (the term is Medvedev's) need a systemic response. Yevkurov’s main problem was that he tried to pour new wine into old barrels that were broken in many places. Meanwhile, it is hard to change some elements of the system without changing the principles of the system as a whole. But changes in the North Caucasus system are impossible as long as the ruling elite’s ideas about this region remain the same.

Former Soviet President Yury Andropov, a favourite of Russia’s present leaders, used to complain that "we know too little about our own country." That opinion is still highly relevant today when we talk about the North Caucasus. Everything that Russia’s central government knows about that region is based on intelligence reports and observations by "competent authorities". The importance of such materials is hard to deny. However, one cannot help noticing that they deal only with persons of deviant conduct, and omit from view the enormous array of people who remain loyal to Russia, the Russian state, Russian law and society. It therefore needs to be understood that without proper academic and applied scientific research in the region (research that is undertaken from time to time by individual enthusiasts without any serious support from the state) it is impossible to form an adequate picture of the situation. For the Caucasus is not only military units, interior ministry troops, the FSB, terrorists, extremists and explosions. It is ordinary people with their daily problems and questions that are not reducible to extremist programs and slogans. But the intelligence officers are not interested in that group of people, they have other problems. Hence the total disappearance of the "Caucasian man in the street" from Russia's current socio-political map. We need to realize that in addition to a soldier, the North Caucasus also needs a sociologist and ethnographer. Otherwise this region will not cease to be a supplier of tragic news.

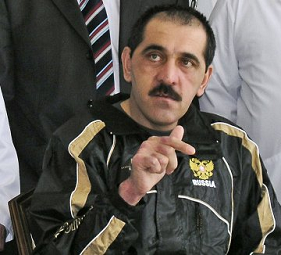

Photo: novayagazeta.ru. (Translation by DM) (P,DM)

DISCUSSION FORUM

|