Chechen traces in the Republic of Mari El Igor Sedoi, special to Prague Watchdog

A few historical facts and numbers

Since Stalin's infamous deportation of Chechens to Siberia and Kazakhstan, another massive outflow of Chechens from their country has intensified in our times, in the period of the first and second wars in Chechnya when the Chechen nation has experienced a tragedy of a similar extent. In December 1994 when the first war broke out, many Chechens still had illusions that there would be neither a war, nor victims, but they were wrong again. The Russian army attacked the sorely-tried country and drowned it in blood, making no difference between civilians and guerillas. As early as in the spring of 1995, anyone who had even a slightest chance tried to leave Chechnya. Since then, with the so called anti-terrorist operation being carried out in the Chechen territory, Chechens are emigrating from their homeland to anywhere where their children and wives, mothers and grandchildren would be safe.

The people of Mari El, an autonomous republic within the Russian Federation located on the river Volga some 600 miles east of Moscow, had some knowledge of who the Chechens are as early as in the 1980th. At that time a few Chechen families settled there doing mostly business and Chechen students began attending local schools. As a matter of fact, almost everybody is in the public eye in Mari El as it is quite a small country by a Russian scale (the population is over 700,000 with some 300,000 living in the capital Yoshkar-Ola). That is why the first Chechens to come to Mari El raised a sincere interest among local people who were eager to learn about the customs and culture of the Caucasians. Moreover, the Chechens actively integrated within the population of Mari El. Since then till the outbreak of the first Chechen war in 1994, several dozen Chechens lived in the republic. But during the first and second wars in Chechnya the number of Chechens in Mariy El rose considerably. Chechen refugees would come to their relatives and friends in Mari El in the hope of surviving hard times, receiving a temporary shelter, start to work and get some help from the state.

Boris Markov, former head of a local territorial body of the Russian Ministry of Federation Affairs and National and Migration Policy, said that in 1999 as many as 222 people were officially registered in the Republic of Mari El as temporally displaced. Today only 42 Chechens are officially registered there, of whom children and minors under 18 years of age make up 20; overall, there are 16 families. Unofficially, the number is three times higher, however.

Official figures suggest that the majority of Chechens have returned home, preferring Chechnya to a peaceful life in Mari El. When asked: “Why? Isn’t it dangerous in Chechnya where even today people risk killing?”, the official just shrugged his shoulders with a bewildered expression. However, these facts say a lot and reveal why Chechens return to their country.

Go back where you came from

Questions concerning “temporally displaced” persons are either ignored in Russia or solved the way whose form and extent forces people without shelter and money to feel beneath their dignity when seeking help at organizations responsible for providing aid.

All responsibilities of the former territorial body of the Russian Ministry of Federation Affairs and National and Migration Policy in Mari El (today the Migration Department under the republic’s Ministry of Interior) were just as follows: registering a refugee, giving him a certificate concerning his registration, passing all the information to Moscow and checking regularly the registered in Mari El. The overwhelming majority of refugee’s appeals have driven no attention because Moscow had allocated no relief funds for refugees in Mari El.

“In 1999 we asked Moscow for money to provide those who came from Chechnya with material aid, but neither that nor any of the following years brought the needed funds,” claims Mr Markov.

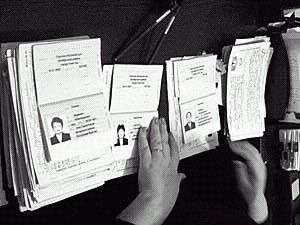

The bodies of the Ministry of Interior that are responsible for the registration of refugees work according to a stereotypical scheme. If you are a lucky refugee to get a temporary residence (available at relatives’ or friends’ place only), you must undergo a humiliating procedure: staying for long hours in queues hoping to get to the right chief of the police or passport section, taking part in animated debates about the reason of your coming to Mari El as well as in an “unobtrusive” talk at the local Criminal Investigation Department where you are asked for leaving your fingerprints. Then every month you must prepare all the documents again, stay in queues for a long time, apply for prolonging your registration, and wait for the answer. And it often takes weeks to wait. In the meantime, you registration runs out so you must pay fines. Make no mistake, there are no reductions for refugees, let alone those from Chechnya.

However, that is not all. Let’s suppose you keep a registration certificate. Any time uniformed people can come to the place stated in your registration and check if you really stay there. Again, you have to undergo a document check with showing all the necessary and unnecessary forms and certificates. Any breach of the Russian legislation leads to a fine and other forms of punishment. And Chechen refugees are the very first such forms are implemented against.

Facing such treatment, many refugees return to their homeland. As officials of the Migration Service claim, despite of a poor state of their department, money for a return ticket can be always found. However, even this service does not work any more, Mr Markov says.

People move, live and hope

According to the Russian legislation, Chechen refugees have been “teleported” to Mari El and other Russian regions because what is claimed to be in Chechnya is not a war, but a special operation against guerilla gangs. What matters here is not the officialese, however. Such play with words is extremely advantageous for the authorities. The legal status of a “refugee” or “forced migrant” guarantees certain privileges, including a shelter, a job, loans and various allowances. But a “temporally displaced person” is an absolutely different thing. As a result of such terminology operations, the reputation of Russia as a state remains unblemished before the world community. What Russia tries to convey is the following: we have some internal trouble dealings with bandits, but refugees in our country? – We can't have them. Again, what a marvellous calculation!

Forty-year-old Maret Daudova came to the capital of Mari El Yoshkar-Ola in 1995, having two young children and expecting the third. Her house used to stand in the centre of Grozny, in the Partizanskaya Street No. 25. Now what remained there is wasteland, even ruins disappeared. The heaviest fights occurred there at the beginning of the first war. In an effort to save her children, Maret decided to leave Chechnya for an unknown republic on the Volga. There she came to the place of her relative who, though having a large family, offered her to live with them. But seeing all the inconveniences of her coming, she went to the Migration Service.

“Asking for help, I came to the Migration Service chief several times, but they always refused to help saying I should go back home. I didn’t want to give up. I came to the Service's office again. I was standing there crying and paying no attention to their showing me the door. Then they must have realized that they just could not get rid of me, accepted my documents and gave me the status of a forced migrant after some time. Shortly before that I had the third baby. The birth went smoothly without any difficulties. I would like to thank all those who helped me expecting nothing for that, especially doctors from the maternity hospital and the antenatal clinic No. 3. Seeing my poor position, ordinary people were bringing me children dresses, clothes, and they even gave me a small baby bed,” Maret says.

Her tattered book of the forced migrant No. 1188-00366-01 reads the following: “Lump sum allowance – 385 roubles”, “Children clothes and shoes – 167 roubles”. There are twelve similar records on material aid for Maret’s children. All in all, since 1995 Maret Daudova has received 4,036 roubles in cash from the state. Of course, she is thankful for that because she knows that she might end up with nothing as many other Chechens spending hours at the Migration Service. Thanks to the money her children grow stronger and healthier. The eldest daughter Lamara is in the 8th class, the other, Kheda, in the 7th class. The third daughter, Khava, is just starting her school and the youngest child, the only son Vakha, is just two years old.

They all live in a small two-room flat in an old two-floor house. Their household is quite modest - old beds, a bedside table, a table and a mirror - but all clean and tidy, and full of children’s laughter and pleasure. The family was provided with the flat by doctor Yuri Sekretarev.

Unexpected guests

The professional career of Anzor Islamov has always been closely linked to the police forces of the Chechen Republic. Having graduated from the police college, Anzor started to work for the crime investigation department in 1984. After several years he was promoted to a high rank. In 1997 he left the job, which almost did not exist any more. Anzor decided to move to his younger brother, who lived in the town of Yoshkar-Ola.

Over the years he has witnessed many things: the dissolution of the Soviet empire, the complicated service during the reign of the first Chechen president D. Dudayev, the hostility and suspicion from the short-lived government of National Revival headed by D. Zavgayev and even the presidency of A. Maskhadov with the subsequent discord. But when suspicious persons started coming to Anzor’s office, asking questions about him and threatening him with punishment, he got fed up with all the harassment. His wife Leila lived in constant fear for the life of her husband and children. Therfore Anzor decided to quite his job and move to his younger brother who run a small business in the Republic of Mari El. After a year, Anzor’s wife Leila and his two sons moved there too.

“I could not take it anymore. Some people accused me that I worked under the regime of Dudayev, other people blamed me for working under the federals. Naturally, I was afraid for my family, and it was hard to see their suffering. So I decided to move to my brother's place”, Anzor tells.

"All Chechens are familiar with the notorious check-point “Kavkaz” close to the village of Samashki. In 1997, during the reign of Aslan Maskhadov, control here was especially harsh. All people crossing the border were closely checked. So was I. Soldiers took me aside to an old caravan where they were investigating me for long, jeering at me, calling me a bandit; then they kept me there for several days. I thought that I would never come out alive, but, surprisingly, they let me out and allowed me to cross the border. I came to Yoshkar-Ola. For several months I was trying to find a job but it was virtually impossible, partly also because the state of my health does not allow me to take any physically exhausting job. Anyway, since then we have been living together with my brother in his one-room apartment, paying him 1500 roubles monthly.... In 2000, our third son – Mohammed - was born. To put it shortly, we are alive. I can’t imagine how we would live without my brother’s help. The doctors say that my health is totally worn down and that I need hospital treatment. But as I’m not registered in the Republic of Mari El I have no medical insurance. Without the insurance it’s impossible to get a treatment. However, recently I was lucky to get a temporary health insurance valid for a month. I will now at least get a physical inspection. In 1998, where we have bad times, we were trying to get a help from federal migration authorities but we had not received any. The deputy chairman of the migration service in the Republic of Mari El put it frankly: 'We have enough problems with our own people. We can’t afford to feed you…' ", Anzor said.

During the second war in Chechnya Anzor lost his house in Grozny. He has nothing to return to and nowhere to go. But he won’t be asking the migration authorities for help and undergo the humiliating process once again.

People meet people

Imran Ismailov lives in the Republic of Mari El and works as deputy editor-in-chief of the local independent paper “Good Neighbours”. The story of this man’s arrival to Mari El resembles a dramatic war novel.

Imran met his future wife when he was working as a correspondent of the “Grozny Worker”, a newspaper published in Ingushetia. Yelena came to Ingushetia as an associate journalist of Radio Free Europe in order to write a series of articles about the situation in Chechnya. Imran helped Yelena to get into Chechnya and after she finished her mission, she invited the Chechen journalist to the Republic of Mari El. Imran he came to see her and decided to stay in Yoshkar-Ola.

Imran was trying to get a job but he encountered serious difficulties. After several failures he finally got a job at the “Good Neighbours” newspaper. Even more complicated was to get the registration allowing him to live in Yoshkar-Ola. He had to bring a pile of various forms and acknowledgments and to go through an AIDS test. The authorities enquired him about the “real motives” behind his decision to move to Yoshkar-Ola. They were not satisfied with the explanation that he moved to marry his Russian wife, Imran said. The policemen even took Imran’s finger and palm prints, not explaining the reason for such extraordinary measures. Regular police visits at the journalist’s flat became routine. Each time policemen were distracted when encountering a man with an intellectual appearance. Apparently, they were expecting someone with more savage looks, someone that would fit in their conception of a “Chechen”.

The paper Imran Ismailov works for often presents views critical towards the current regime of the Republic of Mari. The Mari El government prohibited to publish the paper in the country and for seven months the paper did not come out and the staff, including Imran, were on forced leave. Imran worked on the side and it was his wife Yelena who helped him to overcome those harsh times.

In December 2001 the paper resumed publication but journalists continued to work under extreme pressure from the government. Newspaper is now printed in the neighbouring Kirovsk oblast and although the “Good neighbours” has ambition to be a weekly paper, issues come out once in a month. Imran and his colleagues are facing unreserved hostility from the authorities. Imran´s wife Elena is not an exception.

Does Chechen mean a terrorist?

On June 18 the Mari El evening news brought a stunning story. In a house in the outskirts of Yoshkar-Ola a great storage of ammunition and explosives was found. The tax police, which found the lethal stock, then destroyed it at a safe place. The house was said to belong to Isa Amaliyev, a Chechen living in the Republic of Mary El. Next day, the government friendly newspaper “Mariyskaya Pravda” revealed in an article “Was a terrorist attack being prepared?” more detailed information about the event.

While the inhabitants of the Mari El capital Yoshkar-Ola tensely watched the breath-taking news, the Mari El's terrorist number one was lying at home in a bed with flu and temperature. Would not it be for his wife Margarita Alexandrovna who switched on the evening news, Isa would not know about the fuss caused by him.

Isa Amaliyev by chance arrived in Mari El in 1988. Having graduated from the Armavirski Air School, he worked in the Far East and the Tyumen region. Then he retired from his military service, moved from his flat in Grozny and decided to start his life anew, in a new environment. At that time the political leadership of Mari El started to adhere to a new economic policy. Isa Amaliyev, who had gathered useful experience during his professional career, soon became one of the main protagonists of the new cooperative movement. The then leadership was referring to Amaliyev as an example of a successful entrepreneur and supported his new ideas. The local TV station even shot a clip about Amaliyev, which was called “Manager”.

Obstinacy, industriousness and original thoughts were the qualities that brought Amaliyev from the position of a mere coordinator to one of the greatest businessmen in the Republic of Mari El. Amaliyev established his own company with sewing of work dresses as the main business. He was amongst the first in the Mari El to sign a contract with a foreign partner and in 1992 he started to export his products to Czechoslovakia.

Business was developing very well, the company was expanding, and there were no signs of any crisis whatsoever. That came, however, in 1994. The business and production became unprofitable and Amaliyev wound down his business. The final strike against his business came with the first war in Chechnya.

Apparently, there were people on top who were not much happy about the presence of a successful business run by a Caucasian in the Mari El territory. Because of his Chechen origin and military past, Amaliyev was labelled as a potential gangster. Soon his home and offices became subject to regular and frequent searches and controls by the authorities. Neither the police, nor the Federal Security Service were considerate of Amaliyev's wife and children and even searched through his home with detectors. Nothing illegal had been found, though. In spite of that, Amaliyev’s offices and apartments deposited as a bank collateral, were simply confiscated by the authorities without any official explanation and without issuing any kind of guarantee. Such actions led Amaliyev to final decision to terminate his business entirely.

However, when the fictitious story of a discovered weapon storage took place again, he decided to strike back and called on a news conference.

In front of the gathered journalists he announced that he was not the owner of the lot of land where the weapons had been found. According to Amaliyev, the whole story was fabricated by those who were trying to force him and other Chechens residing in Mari El to leave the republic.

Amaliyev, like many other Chechens living in the Republic of Mari El, has nowhere else to go. During the war in Chechnya he lost his apartment in Grozny as well as his impressive library. In Mari El he has found his new home; his wife was born in Mari El; his daughter and son were born there as well. He says he wants to live in Mari El without fear that his family would be labelled as potential terrorists.

The hunt goes on

Russia is an unpredictable, strange and unexplainable country. The undeclared war in Chechnya, a civil war in fact, caused hundreds of lost and destroyed lives and destinies of people of different nationalities. Along with their Chechen fellowmen many other nationalities – Russians, Armenians, Ukrainians, Jews, Georgians – lived on the Chechen soil prior to the war. Now many of them live scattered around the world, hoping to live a more stable and secure life. They can’t be blamed for that.

People in other countries refer to these people as to Chechens, which in general stands for a terrorist or thug. The Republic of Mari El is not an exception to that. The so called Chechens are periodically exposed to a veritable witch hunt, especially when the elections are approaching or when serious social problems emerge in the country. For example, shortly before the presidential election the Mari El mass media accused the former head of the country that he upholds tight contacts with Chechen rebels, enabling them to buy the S-300 anti-aircraft system that is produced by the local factory. A common inhabitant of Mari El tended to believe such rumours.

The fact that the new political leadership makes more and more frequent use of such kind of anti-Chechen propaganda is certainly alarming and the great hunt for the ill-famed "Chechen trace" seems to have begun in the country. The trace does exist there but is represented by ordinary people who live peacefully, do their business, get married and give birth to children. People who rejoice and despair just like everyone else.

Undoubtedly, a trace will stay also in the soul of a Chechen who arrived in Mari El when having hard times. The period of fighting and destruction will end and many of the Chechens who had found their second home in Mari El will return to the the land of their ancestors. However, the time spent in Mari El will barely be forgotten.

Igor Sedoi is a free-lance journalist.

Translated by Prague Watchdog. (M,K/T) RELATED ARTICLES:

· Basic information about the Republic of Mari El

· Official website of the Government of the Republic of Mari El (in Russian)

· Freedom of Speech in the Republic of Mari El by Center for Journalism in Extreme Situations, Moscow (in Russian)

|